Fortunately, Black History Month basically assures us that young Americans will be taught about the immortals of African-American achievement. The contributions by Americans with the names Frederick Douglass, W.E. B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, George Washington Carver and Martin Luther King Jr. should be known to all teachers and students of American history.

Albeit, the cream rises to the top of any race or generation and should be recognized, yet the common man, so often overlooked or forgotten in the volumes of history, at least deserves a footnote in the making of America and its struggle to survive. Furthermore, the struggles in the streets or an ‘I Have a Dream’ speech would never have been possible without the unselfish contributions that people who were once called ‘men of color’ were willing to make on the fields of every American battle.

Here’s a look at some of those heroes:

The Revolutionary War: The spark that ignited the war is known as the Boston massacre. On March 5, 1770, as an angry "mob" approached the British Customs House (a symbol of Royal authority) to protest alleged mistreatment by British soldiers, a 6-foot- 2-inch "man of color" in the mob stood out like a sore thumb. His name was Crispus Attucks. Attucks shouted, "The best way to get rid of these idlers is to attack their main guard; strike at the root; this is the nest!" The Red coats, already pelted with snowballs and chunks of ice, now encountered clubs and the machete-like blade of a cutlass. Either panicked or peeved, shots rang out from the British muskets. The first to fall was Attucks, the first casualty of the revolution, the first "man of color" to fight and die for an oblique concept called freedom.

During the Revolutionary War period, African Americans fought in the Battle of Bunker Hill, many giving their lives. In the battle, a former slave named Salem Poor distinguished himself so bravely that a petition for his recognition simply stated, "To set forth the particulars of his conduct would be tedious." The petition was signed by 14 officers, including Col. William Prescott, all veterans of the battle at Bunker Hill. Another comment: "He behaved like an experienced officer, a brave and gallant soldier." Regrettably, Poor’s feats of valor were not specifically detailed and are now lost to history.

The War of 1812: Identified as our "‘second War for Independence,’’ the renewed call to arms brought forth a plethora of blacks to fight against the British. Enslaved blacks, however, had other choices: run away and seek freedom among Native American Indians, fight for America, or join the British. Many enslaved men chose His Majesty’s Service seeking a shortcut to freedom; they were disappointed. Most African-Americans fought for the country that tolerated slavery, a nation in its infancy, the United States.

The "Star-Spangled Banner" was penned by Francis Scott Key during the British bombardment of Fort McHenry. More than 60 percent of the soldiers inside the fortification were immigrants, and one out of five of those were African-American. The flag fluttering over the fort that inspired Key had been stitched together by black and white hands. One defender, a runaway 21-year-old slave named William Williams, served with the 38th Infantry Regiment. A British cannonball blew off one of his legs. Williams died two months later in a Baltimore hospital.

In August of 1814, the British pillaged and burned Washington, D.C. An enslaved manservant of President James Madison, Paul Jennings, saved priceless treasures and helped rescue a portrait of George Washington before the British burned down the White House.

Down in bayou country, 6,000 American troops routed the invading British in the fight history calls The Battle of New Orleans. Of the 6,000 American troops, 500 were African-American.

The Mexican War: Abysmal record keeping plagued the entire conflict. Hundreds of American boys were buried in unmarked graves; few were disinterred; none were identified. African-Americans did indeed serve in the military, many consigned to the war to fight in the place of their "masters," but were not officially recognized as soldiers.

Before the dust of battle, Ulysses S. Grant penned a letter to his fiancée about his servant, "I have a black boy to take along as my servant that has been in Mexico. He speaks English, Spanish, and French. He may be very useful where we are going." A young linguist with command of three languages should have served on Grant’s staff, not as his personal valet. Take another shot of whiskey, General.

Absurdly, one old collection of army pay vouchers for private servants sounds like a box of bizarre Crayola Crayons: "a Chinook Indian, one Irish, 17 slaves, 4 Negroes, 34 blacks, 59 darks, six mulattos, and four ‘coppers’." A Negro female named Blanche worked for Lt. Peel of the Second Indiana Volunteers.

Nevertheless, bombs and bullets and cannonballs do not discriminate, and courage is not determined by color. A Washington correspondent reported during the skirmish at Huamantal that a slave named David threw himself in front of an enemy lance, saving his Captain but losing his own life.

Many historians label the duties of African-Americans as "routine’." Jobs as wagon drivers, cooks, nursing the wounded, foraging for food, lariat expertise, entertaining with song and dance, escorting the dead back home, and yes, soliciting Army doctors during Christmas for rum and brandy for the troops, kept the "routine" soldiers busy. In today’s Army these soldiers are considered "support troops’."

The Civil War: The movie "Glory" was a fair depiction, co-starring Morgan Freeman. But unadorned reality paints a different picture. Both North and South hesitated to enlist or arm African-Americans, most of whom were willing to fight for the cause, more unambiguously, the Northern point of view.

Mounting war casualties and the political hypocrisy of an emancipation without fangs surrendered to common sense. By the end of the Civil War, 10 percent of the Union Army was African-American. Roughly 180,000 "men of color" served; 40,000 died, 30,000 of them from disease and/or infections.

Black soldiers proved their mettle at Milliken’s Bend, Petersburg, Port Hudson, and Nashville. The film "Glory" portrayed the suicidal assault on Fort Wagner, S.C., by the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts Volunteers. The frontal assault demanded unbelievable courage: two-thirds of the officers perished, as did half of the soldiers. Confederates abandoned Fort Wagner on Sept. 6, 1863. Union soldiers eventually occupied the garrison without firing a shot.

During the assault on Ft. Wagner a black soldier named William Carney noticed that the standard bearer had been hit and was starting to fall with the American flag. Carney grabbed the colors, raised the flag, and continued on. Wounded several times, men falling to his left and right, Carney scaled the walls of Ft. Wagner and planted the American flag on a parapet. Suddenly aware the 54th was in retreat, and painfully aware he was most likely the only one that made it inside the fort, Carney, too, had to retreat. Wounded twice more, he struggled back to what was left of the 54th. Returning the regiments’ American flag, Carney said, "Boys, I only did my duty; the old flag never touched the ground."Almost 37 years would pass before Sergeant William Carney received the Medal of Honor in 1900. He died in 1908. During the Civil War, 16 black soldiers received the Medal of Honor.

The Spanish-American War: On Feb. 15, 1898, the USS Maine exploded in Havana harbor. American lives were lost; America seemed to want this war, so to war we went. However, war requires a military. Navy forces were adequate, but an Army of 26,000 men and 2,000 officers would not suffice as a fear factor.

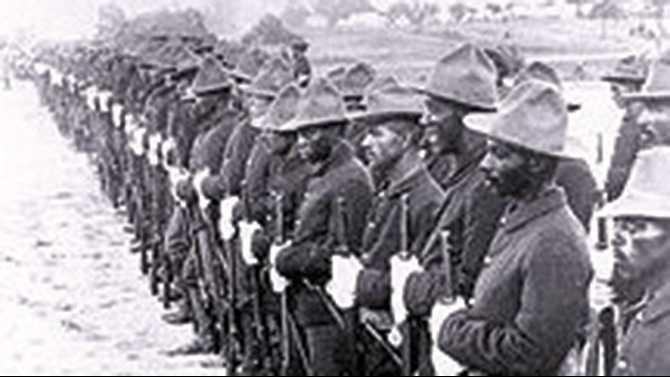

Among the first units to receive the call were the four black regiments of the West. Rational then but laughable today, the War Department considered black soldiers immune to tropic disease and not restrained by humid temperatures. There was even a "push" to recruit even more blacks because of their "immunity."

Despite from the sheer stupidity of the War Department and the racial tensions encountered at several stateside staging areas, the African-American soldier once again proved his mettle in Cuba. Within two days of landing near Santiago, the 10th Cavalry was called from reserve to fight in the battle at Las Guasimas. Their courage assaulting fortified positions was lauded by white officers.

Publicity and recognition for the black soldiers were overshadowed by the 1st Volunteer Cavalry, better known as the Rough Riders. Theodore Roosevelt led the Rough Riders, and he understood publicity and glory and the press.

No denigration was meant concerning the Rough Riders. Their courage and grit was unquestionable, as was Roosevelt’s tenacity and coolness of command, but the Rough Riders’ legendary assault up San Juan Hill ran into immediate trouble. Assailed from all sides and in peril of being cut to pieces, the Rough Riders needed reinforcement. In the distance, the 9th and 10th Cavalry hit a dead run to relieve pressure on the Rough Riders. Under merciless gunfire and taking casualties, the black soldiers pressed their charge.

A New York journalist reported, "They fired as they sprinted, their aim was splendid. Their coolness was superb and their courage aroused the admiration of their comrades." One of Roosevelt’s soldiers on San Juan Hill said it best, "If it hadn’t been for the black cavalry, the Rough Riders would have been exterminated."

Five soldiers of the 10th Cavalry received the Medal of Honor. Twenty five others were awarded the Certificate of Merit.

World War One: The Great War, perhaps the great opportunity, again, for black soldiers to validate their courage in combat. Of the 380,000 African-Americans who served in World War I, 200,000 were sent to Europe and roughly 42,000 saw combat.

Most notable were The Harlem Hellfighters, New York’s fighting 369th all-black Infantry. Its motto was rough for 1917; "G.. d..., let’s go!’" But they were a rough assemblage of men. They had to be. Maj. Warner Ross described their arrival on the front, "Stones, dirt, shrapnel, limbs and trees filled the air. The sounds and concussions alone were enough to kill you. The flashes of fire, the metallic crack of explosives, the awful explosions that dug holes 15 and 20 feet in diameter, and the utter and complete pandemonium and the stench of hell….your friends blown to bits, the pieces dropping near you."

Into hell, the 369th was paired with the French near Minacourt, France. On the night of May 14, 1917, Privates Needham Roberts and Henry Johnson were destined to become legends. Both were standing watch when a German grenade landed in their trench. Needham was badly wounded, leaving Johnson to face the German onslaught on his own.

As Roberts struggled to evade capture, Johnson sprang into action. His story as told by Maj. Arthur Little: "The little soldier from Albany came down like a wildcat upon the Germans. He unsheathed his bolo knife, and as his knife landed upon the shoulders of that ill-fated Boche, the blade of the bolo knife was buried to the hilt through the crown of the German’s head."

The fighting was hand-to-hand, fierce and unforgiving. Singlehandedly, Johnson killed or wounded 24 enemy soldiers. The story gained front-page coverage in America as "The Battle of Henry Johnson."

Martin Green, in the New York Evening World: "Johnson was wounded 3 times, he clubbed Germans with the butt of his rifle; he shot Germans and carved them with his bolo knife. As the enemy fell into disorderly retreat, Johnson, three times wounded, sank to the ground, grabbed a hand grenade alongside his prostrate body, and literally blew one of the fleeing Germans to fragments."

Johnson and Roberts were later presented the French Medal of Honor, the Croix de Guerre. They were the first American soldiers, black or white, to be so honored.

During the Battle of Belleau Wood, a panicked French general ordered his French soldiers and the Harlem Hellfighters to retreat. The 369th commanding officer, Col. William Hayward, responded, "Turn back? I should say not! My men never retire. They go forward or they die!" The Harlem Hellfighters spent 191 days in frontline trenches, more than any other American unit; none were captured, and the Germans never gained one inch of ground.

World War II, Korea, Just Cause, Grenada, The Gulf War, Afghanistan and Iraq: Search the internet, hit the history books, visit your library, study and read the true cost of freedom, and the struggle for freedom during Black History Month. An entire newspaper would be needed to properly honor each conflict, each story. Nevertheless, as a Vietnam veteran, permit me to comment on race and war, the tint of a soldiers’ skin, and the two-way street called racism.

The Vietnam War: Vietnam was a heartless undertaking, and ultimately an unappreciated mission. I served with numerous black soldiers, and yes, suspicion and distrust and lingering beliefs from childhood clouded appropriate acquiescence from both sides of the fence. But a common foe, coming across the fence or through the barbed wire, bonded men of all color in a communal fight for survival.

In war, the pigment of your copilot is not important. The white or black tint of the skin hunkered down next to you in the bunker at Khe Sanh is insignificant. The color of a seaman’s deck shirt, not his skin, can save your life on the hazardous deck of an aircraft carrier. The color of the tank crew rushing to your aid during the Battle for Hue is irrelevant.

Lily white, charcoal black, Native American red, Asian brown or Chinese yellow, we were essentially all the same, because we all bled the same color blood. War is the great equalizer. It does not discriminate, it will not judge, it favors no religion, it harbors no grudge, it harbors not one drop of compassion.

Soldiers, sailors and airmen depend on each other. We are trained to care for and take care of the warriors next to us, regardless of race, creed, or religion. The man next to you is your safe ticket home, your life-support in combat, your brother, your sister, an individual willing to kill so that you may live.

Yet after punching that safe ticket home, a soldier arrives in a land still divided by race, mistrust, and politically correct nothingness. Divided, we cannot stand. We are all overdue to bury the racial hatchet to face the common enemies at the gates: division, despondency, derisiveness, and dependency.