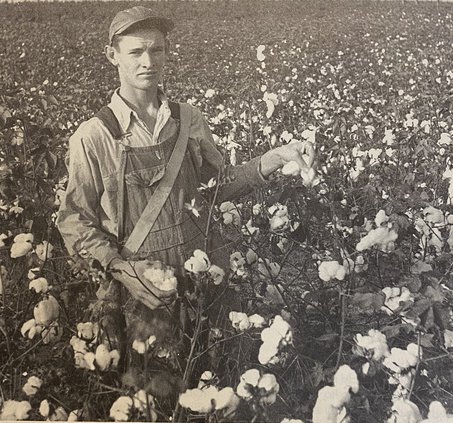

Before the film industry boomed and the area was packed with opportunities in technology and manufacturing career fields, it was agriculture that reigned supreme in Newton County, and cotton was king.

But how did cotton lose its place among area farmers’ top crops? It was upheaval that came in the form of a gray, quarter-inch insect known as the boll weevil.

Cotton ascends to throne

Local historians believe cotton began its rise to the throne among cash crops in Newton County in the mid 1800s, shortly after Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793.

Historical documents from the 1820s showed livestock was a major occupation of the county’s earliest settlers. The estates of seven Newton County men who died during the 1820s included an estimated 463 cattle, 26 horses and 255 hogs. At the time, cotton and corn seemed to be of little importance.

About 10 years later, the local cotton crop began to grow. Documents showed three sizable estates of men who died in the 1830s were home to a significant amount of cotton production.

After the Civil War, the local cotton crop spiked and eventually took over as Newton County’s top product. Historians say cotton gins were located all across the county, in Covington, Mansfield, Newborn and Starrsville, and there was another built a few miles north of Oxford.

Historians suggest cotton production peaked around the start of World War I, which led to local farmers entering the 1920s with resounding optimism for their prized crop.

But in 1921 — exactly 100 years ago — the boll weevil changed everything in Newton County.

Insect invades U.S.

A boll weevil (Anthonomus grandis), which is a beetle that feeds on cotton buds and flowers, is considered to be native to Central Mexico. It is believed to have migrated to the U.S. in 1892. In 1903, the chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture testified before Congress that the insect’s outbreaks were a “wave of evil.”

Boll weevils eventually reached Alabama in 1909 and Georgia only a year or two later.

Today, a monument dedicated to the boll weevil sets in downtown Enterprise, Alabama. It was erected in 1919 to show their appreciation for the insect and its unlikely positive impact on the area’s agriculture and economy.

According to past reports, farmers were losing whole crops of cotton by 1918, just a few years after the insect infiltrated Coffee County, Alabama. A man named H. M. Sessions saw this as an opportunity to shift the area’s focus to peanut farming. After Sessions convinced another farmer to back his venture, the first crop paid off their debts and was bought by farmers seeking to change to peanut farming. Cotton was eventually grown again, but farmers learned to diversify their crops — a practice that brought in new money.

The same appreciation for the insect would not be found in Newton County.

Boll weevil bites Newton’s cotton production

While some of Newton County’s farmers took advice to diversify their crops rather than depend on their single cotton crop, many did not until the enormous impact of a minuscule boll weevil took its toll on the area.

Within one year, from 1920 to 1921, Newton County’s cotton production decreased by 70% — 18,115 bales ginned to only 5,257 bales ginned.

The boll weevil sent many families into economic turmoil.

An example of this was seen through Aubry C. Ewing, whose family farmed in Covington. The Ewings’ cotton crop was virtually destroyed as no significant amount of cotton could be picked. Historians record that the Ewings continued farming but did not plant cotton again until 1924 when there were more effective methods to combat the boll weevil.

Many farmers lost everything. Families were displaced and people who once farmed for a living were forced to find “public work” in textile mills and other industries across the area. Some even packed their belongings, moved north and discovered opportunities surrounding the developing automobile industry in Detroit, Michigan. In fact, while many people were moving across the country from the “Dust Bowl” to California in the 1930s, there was another great migration taking place: people from the South were leaving for the North to work industrial jobs — all thanks to the boll weevil.

Treatment, eradication of boll weevil

Before Newton County’s cotton crop was devastated by the boll weevil, a meeting was held for area farmers to learn how to fight the dreaded insect that would soon infiltrate their crops. A man only known as “Mr. Ward” in historical documents explained to local farmers how he had been fighting the pest for the previous three years in south Georgia.

At the time, The Covington News reported approximately 75 people attended and learned the three ways to control boll weevil infestation, which included:

• Pick up the squares (flower buds) which fell on the ground after being infested by larval boll weevil.

• Poison with a mixture of insecticide and molasses, and then dab onto the squares of the plant.

• Apply poison in dust form to the whole plant.

Unfortunately, the poison treatment wasn’t feasible for most farmers within the county, which led to a dramatic decline in cotton production.

Years later, a more reasonable treatment method was introduced which allowed many Newton farmers to bring back a portion of their cotton production.

Following World War II, the development of new pesticides such as Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, commonly known as DDT, enabled U.S. farmers again to grow cotton as an economic crop. DDT was initially extremely effective, but U.S. weevil populations developed resistance by the mid-1950s.

After the boll weevil cost farmers billions of dollars in revenue, the National Cotton Council of Agriculture reportedly crafted a piece of legislation in 1958 that called for the expansion of cotton research and the eradication of the boll weevil.

In 1978, a large-scale test was begun in the states of North Carolina and Virginia to determine the feasibility of eradication.

Based on the test’s success, area-wide programs were reportedly started in the 1980s to eradicate the insect from whole regions, based on cooperative effort by all growers together with the assistance of the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

The program proved to be successful in all cotton-growing states with the exception of Texas, but most of the state is considered free of boll weevils. Problems along the southern border with Mexico have delayed eradication in the extreme southern portions of the state.

Follow-up programs are reportedly in place in all cotton-growing states to prevent the reintroduction of the pest.

Insect’s local impact today?

No one should expect Newton County to raise its own monument to the boll weevil, as the insect successfully wrecked the local economy a century ago. Nonetheless, should area residents be somewhat thankful for the boll weevil?

If not for the cotton killer, what would Newton County’s economy look like today? It’s nearly impossible to know, but there’s a chance it would be completely different.

If not for the insect, the area could have still been centered around the agricultural industry and allow cotton to remain king. However, the area may also have never become “Hollywood of the South” or home to billion-dollar industries such as Facebook and Takeda.