Born in 1929 in Toledo, Ohio, a short six weeks later Richard Grimes and his family moved to White Plains, Georgia. He recalled, “My dad had a large dairy farm in White Plains, several hundred acres. He delivered milk to markets in Atlanta and Augusta. We did well, even though our country was gripped by the Great Depression. However, by 1935 my father was pouring milk down a sewer because the milk market bottomed. Luckily he found employment with Toledo Scales in Ashville, NC. And, yes, we took a milk cow with us.”

As the winds of war swept across Europe and Asia, Toledo Scales home office transferred Grimes’ father back to Ohio. “We understood a war was on the horizon,” he said. “The German military victories had been in the news for a long time. We even heard the news in church. I was at a Boy Scout camp on Dec. 7, 1941. Our scout master informed us of the attack and we were all old enough to understand that Pearl Harbor meant our country was at war.”

Teenager Richard Grimes kept track of WWII. He said, “It’s as vivid as yesterday. I followed the news of Rommel’s defeat in North Africa, the D-Day Invasion of Normandy, Iwo and Okinawa, then of course the two atomic bombs. I was 16 years old and knew at 17 I’d be gone, probably for the Invasion of Japan. If it hadn’t been for those two atomic bombs, I probably wouldn’t be here today.”

The family returned to Georgia after the war. Grimes said with a smile, “Dad didn’t care too much for Yankees. Anyway, I finished high school in 1947, the Salutatorian of 15 graduates at Arabi High School. I wasn’t the smartest, just the least dumbest.”

Grimes received a scholarship to the University of Georgia. He recalled, “Back then all males took ROTC. I majored in chemistry and graduated as a distinguished military graduate in 1951.” Due to his extraordinary accomplishments, Grimes received a regular commission in the Army instead of a reserve commission. A year earlier North Korea invaded South Korea; a war was on. “I figured that would be my next port-of-call,” Grimes said. “While I was awaiting orders, I found out I could go to jump school at Fort Benning. So I did.”

Country boy 2nd Lt. Richard Grimes was soon jumping out of airplanes. “Well, jump pay added $100 to my paycheck and as newlyweds we sure needed it.” Grimes met his wife, Ann, at the University of Georgia. “Ann was an English major. That’s a good fiancé to have if you’re going to college,” he said, grinning.

On jumping out of planes: “It’s not a natural thing to do, that’s for sure. But the training was excellent; jump school was my favorite. Your first 3 seconds after jumping feels like an eternity, but serene, peaceful, very quiet. Then, wham! The chute opens. We wore shoulder padding to prevent bruising. Our padding…well, the padding was store-bought and very feminine.”

Fort Knox, Kentucky: “At Fort Knox I took an 18 week basic officer’s course in armored tactics and recon. We learned map reading plus pioneering. We utilized two tanks, our main battle tank the M4E8 Sherman with a 500hp engine, and the smaller M-24 General Sheridan with 2 Cadillac engines. It’s like comparing a Model-T to a Corvette.”

Fort Campbell, KY: “I joined 11th Airborne, the 710th tank battalion as a platoon leader. We all expected to go to Korea. I had buddies in Korea, some didn’t make it home. The West Point class of 1947 was absolutely decimated. They lost so many 2nd Lieutenants in Korea the class of ’47 doesn’t even hold reunions. Not enough of them left alive. Out of the 97 junior officers I trained with 95 went to Korea and the other two were sent to Germany. I was one of the two.”

Kronach, Germany: Grimes joins the combination police/military unit known as the Constabulary. Grimes explains, “After WWII there were a lot of 18 and 19 year old American soldiers with nothing to do. That caused problems. General Patton once stated, ‘We need to show the Germans who won the war.’ He didn’t mean as retribution, but to get the troops back to a ‘spit and shine’ mentality. The army got the boys home and the Constabulary worked with the German police to enforce the law and protect a 1200 mile long border.”

Grimes recalled the assumptions during the Korean War and Cold War. “We knew the Russians had advisors in Korea and we expected them to come at us in Germany. In truth, we were expendable. My wife kept a packed suitcase in the car at all times. In case of ‘emergency’, she was to head for the Rhine River; that’s where the Allies had chosen to hold the line.”

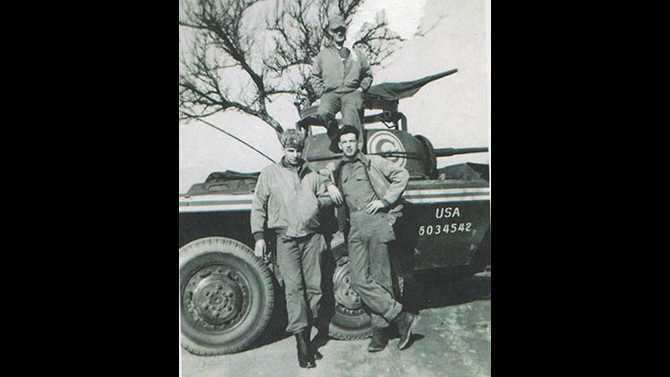

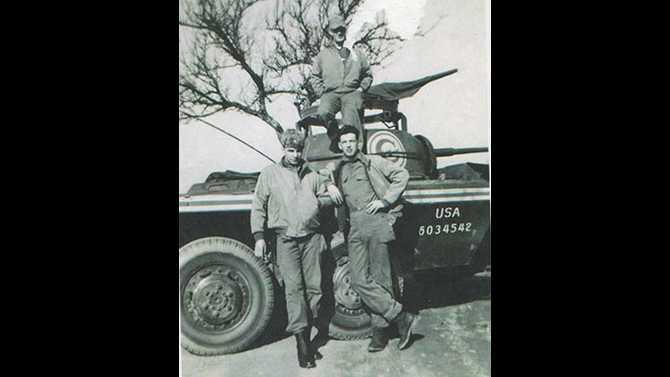

The Constabulary wore helmets with a big yellow ‘C’ on front ringed by a yellow circle. They were known as the Circle C Cowboys. The Circle C Cowboys could hit 80mph on the autobahn in their M-8 armored cars, with a 37mm cannon and .50 caliber machine gun. Grimes said, “We drove jeeps, too, with the windshield down. We installed a piece of steel on the hoods to snap the piano wires that the East Germans and Russians strung across roads. By the way, Germany has two seasons, the 4th of July and winter. Very cold. Anyway, I recall one night we had about 100 rolling stock railcars on our side of the border. The Russians and East Germans laid track, snuck across the DMZ with a locomotive and stole every one of the railcars.” Having served a required 3 years in a combat branch, Grimes headed back to the states as a 1st Lieutenant. His silver bars were pinned on his shoulders by the legendary airborne officer, General James Gavin.

Fort McClellan, Alabama – Grimes recalled, “With a degree in chemistry I guess I was destined for the Chemical Corps, that’s the NBC, nuclear, biological, and chemical outfit of the US Army. Guess they liked what they saw because I became an instructor until 1957.” That same year the Army wanted Grimes to earn a Master’s Degree, at Georgia Tech. He recalled, “I told them they couldn’t do that to a UGA graduate; it just wasn’t kosher and bordered on cruel and unusual punishment.” Told that’s where his paycheck would be sent, then-Captain Richard Grimes stomached 2 years of Georgia Tech and in 1959 received his Master’s Degree in Management.

Back to Fort McClellan, Alabama – Grimes explained, “We tested chemical warfare systems, safety, always safety, first. If you can manufacture beer you can manufacture biological agents; if you can manufacture paint you can manufacture nerve gas. Nerve gas was discovered in Germany. It’s a good thing the professor left good notes because the next morning everybody in the lab was dead.”

Grimes worked with numerous NBC agents, including Tularemia (rabbit fever), mustard gas, nerve gas, and anthrax. On anthrax: “My father-in-law worked for the US Government at a meat packing plant. If a worker contracted anthrax, they would just take him home, wish him luck then plan for his funeral. Anthrax is a bovine disease from cattle. People are not immune to anthrax. It’s deadly; a couple spores can kill a person.”

Summer, 1963: Then-Major Richard Grimes is ordered to Vietnam as a chemical advisor to the 2nd Vietnamese Division, and for his rendezvous with a defoliant called Agent Orange. He recalled, “I was quartered in Da Nang but worked mainly with remote outposts. We fortified them with barrels of napalm. Soldiers will come through machine gun fire, claymore mines, hand grenades, but not flame. It’s a great deterrent.”

The program called Ranch Hand: “Ranch Hand was Agent Orange, plain and simple. The delivery systems included artillery shells, generators to push the chemical downwind, but usually delivered from spray tanks on choppers or aircraft. I remember we were aboard a C-123 less than 100 feet from the ground, the back ramp down, the nozzles spraying Agent Orange, and my buddy lays down on the ramp and tells me to hold his feet so he can take pictures of the chemical being sprayed. Well, I did, but an enlisted guy said, ‘Major, that’s not going to do you any good.’ I think he was telling me if my buddy slid out, so would I.”

Grimes cautiously defended the use of Agent Orange. “The side effects, of course, turned out to be horrible, but it also saved a lot of lives. We could defoliate the areas around old French fortifications littered with land mines covered by foliage. Many outposts bordered dense jungle; the defoliation saved them from being overrun. It denied the VC crop production and concealment.”

Grimes returned home in May of 1964. A full-accounting of Richard Grimes’ service to his country is not possible in a newspaper column, but completing his career included – Defense General Supply Center in Richmond, Virginia, Command and General Staff College at Leavenworth to include a promotion to Lt. Colonel, a stint at the Pentagon in his own words, “as an ‘action’ officer, not a ‘horse holder’ (General’s Aide), an exchange officer to England serving in Her Majesties’ Service to teach and lecture at Winterbourne, Sandhurst Royal Military Academy, and prestigious Cambridge University.

He recalled, “Many places had signs posted ‘For U.K. Eyes Only’ which caused a lot of British officers to ask, ‘Why is this Yank teaching us?’ I enjoyed England, good people, good soldiers.”

Lt. Colonel Richard Grimes retired in 1971 after serving as the Director for Services at the Army Depot at Fort Gilliam, GA. “We also oversaw the repair of choppers returned from Vietnam,” he said. “The horror of war was evident by dried blood, even body parts. But, we did manage one emergency….the Army was actually running out of the canvas sand bags in Vietnam. So, we are credited with solving the nation’s first, and hopefully last, national sandbag emergency!”

Humor has served this patriot well. Suffering from neuropathy in his legs and arms, he loses balance and all feeling in his arms and legs so badly it’s difficult for him to go through papers, like money or bills. He is on 100% disability due to the effects of Agent Orange.

In civilian life, Lt. Colonel Grimes taught economics and accounting at Clayton State University before teaching 21 years at DeKalb College. He still does taxes for a few ‘friends’.

His closing comments: “Like nuclear warfare, a chemical or biological exchange will hopefully never be needed. I’m a chemist, trained and exposed to what these weapons can do. I came home one day from a field exercise when I was at Fort McClellan and took off my clothes in the laundry room. Well, I must have been careless when on the field. My wife stepped on the pile of clothes and got a big blister on her heal from mustard gas. Not a pretty sight, and not a happy wife, I may add.”

The couples’ son, Greg Grimes, retired as a ‘full-bird’ Colonel, one rank above Lt. Colonel. Asked if his son, Colonel Greg Grimes, ever reminds his father that he’s outranked, Lt. Colonel Richard Grimes produced an amusing smile and stated, “Yeah, every chance he gets.”

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran, columnist and freelance writer. You can reach him at aveteransstory@gmail.com or aveteransstory.us.