December, 1923, Atlanta: Jim Butler enters the world in an apartment house at the corner of Memorial Drive and Moreland Avenue. His dad maintained a job during the Great Depression so in Jim’s words, “Our family did okay.” Tech High School awarded Jim a diploma in the spring of ’42. Hired by Rich’s Department Store, he listened to the stories of a co-worker who had joined Navy aviation. Rather than be drafted as a ground-pounder, by September Jim had taken and passed his physical and mental tests for pilot training with the U.S. Navy.

February, 1942, Athens, Ga.: “As trainees we stayed in an old hotel on the main square,” Jim said. “We were up at 5:00am, ran to breakfast, ran to the gym; ran to the airstrip for ground school. The program was CPT, meaning Civilian Pilot Training. I’d never flown before but became hooked on aviation the first time I went up in a Piper Cub. I loved flying and soloed after eight hours.”

Jim’s favorite maneuver at CPT was the Pylon 8. “We picked out two pine trees and weaved around them in a figure eight,” he recalled, grinning. “I enjoyed the training, but after about two months my instructors said, ‘I’ll pass you, but you’ll never make it as a pilot.’ Guess I fooled him.”

Sent for secondary training in Clarksville, Tennessee, Jim stated, “The weather was horrible. We stayed socked-in but we weren’t too upset about that because the only planes we had were two flimsy biplanes. They appeared to be homemade contraptions with different engines, different parts, and different instruments. I don’t think they even had a classification. Those planes looked a bit unreliable to me. I flew a total of three hours in two months.”

Next stop: Norman, Oklahoma, E-base: “I flew the legendary Stearman biplane to learn basic aerobatics before moving on to Ellyson Field in Pensacola. At Ellyson we trained on the old Vultee BT-13 Valiant, better known as the Vibrator,” he said. “That was the first time we flew at night. It was just another part of the training, not scary at all. Then we moved on to Whitting Field for advanced flying and instrument training. We had a great plane too, the SNJ Texan.”

Gunnery and bombing tactics were mastered at Barin Naval Air Station in Alabama. “We actually called it Bloody Barin due to pilot losses,” Jim said. His first instructor in Athens had to eat crow; Jim earned his wings and was commissioned an Ensign in 1944.

Ensign Jim Butler wanted fighters; he got the best, the celebrated F6F Hellcat. “That was my favorite,” he said. “I trained in a Hellcat before being sent to the Great Lakes Naval Air Station in Chicago. The Navy had an aircraft carrier on Lake Michigan called the USS Wolverine, a converted paddle-wheeler coal-burning steamer. Ugly thing, it was. I did okay but have to admit my legs shook like Jello after my first couple of landings.”

Next stop: Norfolk, Virginia for duty on the ‘baby flattop,’ USS Wake Island. “That didn’t last long,” Jim said. “Within a month I was reassigned to Atlantic City to a group of unassigned pilots that eventually became VF-92.” Seeing the world, or at least the East Coast, Jim received orders for Quonset Point near Groton, Connecticut. “We sharpened our skills on a full-sized carrier, the USS Croatan, plus attempted our first night landings on a carrier deck. That, was a bit scary….it was overcast, no moon, no stars, and no landing lights. The only illumination was flashlights sitting atop blocks on each side of the flight deck. That was a little tricky, but we did okay.”

Alameda, California: Jim Butler boards the troop ship USS General John Pope to cross the Pacific Ocean, first to Guam, then down to Saipan for duty aboard an aircraft carrier. “The Japanese Kamikazes were taking a toll on aircraft carriers,” Jim said. “I was assigned two different carriers but neither one made it back to Saipan. We finally departed on the newer USS Lexington and eventually ended up in Tokyo Bay. The Japanese had surrendered while we were at Saipan yet in less than a month we sailed into their home bay. I’ll say this, Tokyo Bay is one gigantic body of water!”

Tokyo, Japan, a month after the end of hostilities: “I was surprised,” Jim said. “The Japanese were a defeated people but they treated us very respectfully; we had no trouble at all. Some of Tokyo was a wasteland, but other parts to the city were untouched by the war. Yokohama was a different story, total devastation, hardly a cinder block left standing.”

WWII was over, yet Jim Butler had more close calls in Japan than at any other time. “I signed out a Hellcat from the Yokosuka Naval Base then flew over Mount Fuji, way too low, I suddenly found out. A downdraft from the volcano cone pulled me down inside the crater, scared me to death. I had to push full-throttle and pull up hard to avoid becoming a grease spot on the side of Mount Fuji. If that wasn’t enough, I was later flying in our carrier’s quadrant with our entire air group when another carrier’s air group inadvertently flew out of their quadrant into ours. I was flying tail-end Charlie and watching the guy next to me but noticed our flight leader abruptly going into a power dive as if try to get away from something. When I looked up the sky was full of aircraft coming right at me. I thought I was done for. I had to fishtail, basically slipping and sliding through a solid mass of airplanes. Luckily, we all made it out alive.”

Then there were the typhoons.

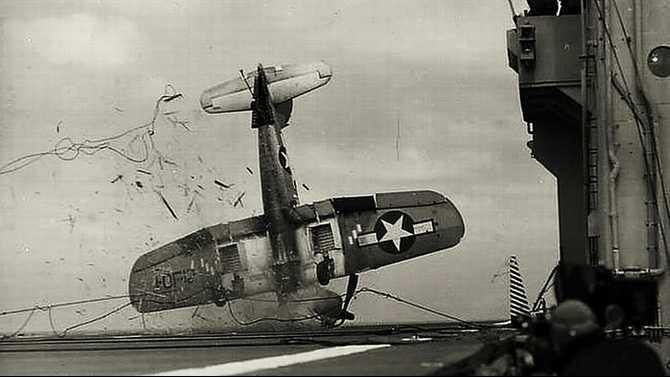

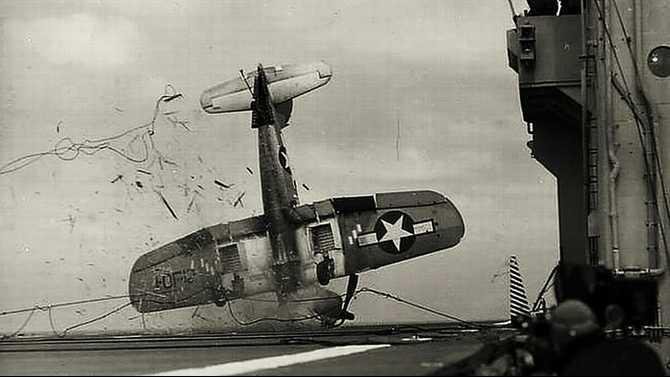

“We were on the edge of one typhoon when we received an alert call a sailor on a destroyer had been washed overboard. I was launched to help the search. Sadly, we didn’t find the poor guy, but coming back the carrier deck was pitching and rolling like a cork riding a tidal wave. My approach was good, but about the time I cut my engine the ship rolled and I hit hard, more or less sideways, and Bam! My tires blew. I was okay but I didn’t fancy another landing in a typhoon.”

Home in June of ’46, Jim Butler returned to college, married, earned an Associate’s Degree, and found a steady job at the Warren Co. until the North Koreans decided South Korea was ripe for the pickins’ in June of 1950. Called back to active duty, Jim soon found himself in the saddle of a F4F Gull-winged Corsair. “The Corsair was a heck of a fighter,” he said. A lot of pilots lost their lives before the kinks were worked out, but it proved invaluable in Korea.”

Luckily, Jim missed Korea and sailed the Mediterranean aboard the USS Tarawa. “I guess my job was protecting us from the Russians,” he said, smiling. After two and half years back in uniform, Jim Butler left the Navy for a successful career as a plumbing engineer. “I designed the plumbing for the first Atlanta Stadium, churches, schools, the Covington City Hall, the AJC’s new building, and many more before finally retiring in 1986.”

Asked his final thoughts, Jim stated, “I’ll be 91 in December. I’ve had a good life and I loved the Navy. As a fighter pilot, I always wanted to see exactly how good I really was, but it just wasn’t in the cards. I consider it a great honor having served as Navy pilot. But I am saddened about what’s going on in our country. We keep fighting wars we don’t want to win. When an enemy is motivated by religion, and especially when that religion tells them that it’s okay to kill the non-believers, well, you have to take the war to them or they will bring it to you. The only other alternative is Armageddon.”

Jim Butler survived 125 carrier landings. Although there were several crash landings by VF-92, all the pilots survived WWII.

In war, heroics, outcomes, and casualties hit the headlines, but the cost of freedom is measured by so much more. Men and women trained for combat may never see combat, but they signed the dotted line and are willing to give it all if necessary. War, takes a toll, and not just in battle. Over 18,000 young men lost their lives in pilot training during WWII in the continental United States alone. Another 1,000 aircraft and crews simply disappeared in transit to Europe or the Pacific. In all, during the 2nd World War there were over 53,000 aircraft accidents, many fatal. Freedom, even in peace time, is not cheap.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran, columnist and freelance writer. You can reach him at aveteransstory@gmail.com or aveteransstory.us.