Harriman, TN - 1966: As one of the eager seniors attending Career Day at Harriman High School, Howard Hendrickson gave the Army recruiter an opportunity to bend his ear. Howard stated, “He kept talking about how bad basic training could be so I didn’t even think about joining up.” Tech School for data processing seemed the better alternative. “I had the training,” he said. “But the albatross around my neck was a draft card with a 1A classification. There wasn’t a job in East Tennessee to be had.”

A tempting job market in Atlanta enticed Howard into the Peach State. “I got a job at Mead on Marietta Street then pestered the Employment Manager for months until I got a position in data processing using the old IBM card system. That ended in April 1968 when I got a notice to report to the Knoxville Induction Center.” Howard was still registered for the draft in Tennessee. “My older brother, Ernest, was inducted at the same time. We passed our physicals and two weeks later received ‘greetings’ from Uncle Sam. We were in basic training within a month at Fort Campbell, KY.”

“Ernest had a weight problem so they took potatoes and other starchy foods out of his diet. In late evenings as other guys enjoyed their time off duty, I was outside running with Ernest. He did great and lost the weight.” Howard remembered the heat and his drill instructors. “It was so hot and we sweated so much our green fatigues turned a salty white. But I will say good things about our drill instructors. They were combat veterans of Vietnam and taught us well. They knew what they were talking about; they knew how to keep us alive.”

After basic, Ernest reported to Fort Riley, KS. Howard was assigned to Aschefberg, Germany after completing heavy equipment maintenance courses. He recalled, “I joined a combat engineering battalion but that didn’t last long . The Army issued our new platoon leader an old Jeep and he asked me to be his driver. That was a great way to see Germany so I jumped at the chance. The jeep didn’t have a heater. Needless to say, it was a bit cold.”

After a year in Germany Howard was sent home in November of 1969 for a thirty day leave. “I had orders for Vietnam but I wasn’t too happy about it,” he said. “My dad wasn’t either. We’d seen the war footage on TV and didn’t like what we saw. My father and two of his brothers served in World War Two, but that was a different war. Dad didn’t see any plan for winning the war in Vietnam and too many boys were dying because of it. Uncharacteristic for my father, he mentioned how some boys were going to Canada to avoid the war.”

Howard chose to serve his country. “I told my father if he and his two brothers served, then it was my responsibility to do the right thing. He and I both knew it was a political war, and considering what’s going on now our leaders haven’t learned a darn thing.”

Howard attended a two week jungle combat course at Fort Lewis, WA before landing at Bien Hoa, Vietnam via Hawaii and Guam. “From Bien Hoa I took a C-130 to Pleiku,” he said. “They loaded us on an Army bus for a crosstown trip to the 4th Infantry Division’s HQ. During the trip a grenade hit against the bus but the metal guards and bars protected us. It exploded harmlessly. Welcome to Vietnam.”

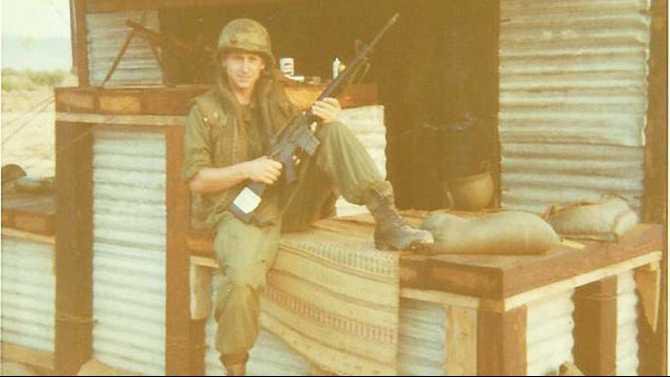

Howard received 14 days of ‘in-country’ training to learn the ropes for survival. “They were teaching us to be smart because a lot of new guys wanted to be heroes but they ended up dead.” Howard was not happy with his issued M-16. “It would jam on rock and roll (fully automatic) so I complained. I was told, ‘then don’t use it on rock and roll; just shoot what you can see.’ Uh-huh, like you could see in the jungle!”

Howard’s Jeep driver experience in Germany followed him to Vietnam, temporarily. “I joined Charlie Company, 4th Engineering Battalion, as a Jeep driver,” he stated. Unlike Germany, it was NOT a good way to see the country. Luckily, I only drove on base.”

The base was An Khe. “When we got hit it was always after ‘lights out’ at 2200 (10:00pm). The rockets and mortars would come in and we’d man the bunkers, sometimes for an hour, sometimes all night.” After a brief pause Howard said, “Even now after ‘lights out’ at home I feel like going to a bunker. Things like that just stay with you.”

Jeep driver half the time; a combat engineer in the field the other half. “We took choppers to selected sites for landing zones then used C-4 explosives, Bangalore torpedoes, and chain saws to clear an area. The first night in the field I woke up the next morning with jungle rot on my feet; blisters as big as my thumb. I spent a couple days in the hospital. Cleanliness was important in Nam and I’m usually a very clean person, but bathing in a bomb crater with water dirtier than you still felt good.”

May, 1970 – America invades Cambodia. “My infantry unit was airlifted then dropped right in the middle of an enemy training camp. We found wood carvings of American aircraft, Hueys, Chinooks, a gunship, fighter jets, even B-52s. The North Vietnamese used these wooden models for identification training. We lost some guys in firefights and killed some sappers trying to sneak inside our perimeter to hit the command post with explosive charges. Standing guard in the jungle is spooky, all kinds of sounds out there, some human.”

Howard recalled the ugliness of war. “A Chinook resupply chopper had difficulty finding good grounding because of all the dust and hit sort of cockeyed. The pilot cut the engine then the chopper tilted over. The rotor blades broke off and went everywhere. An engineering officer was decapitated, one NCO was disemboweled and another mortally wounded. That really bothered me. The other thing was finding box after box of enemy supplies shipped from California, bandages, food, blankets……I don’t know how the stuff got there but lettering on the boxes identified an anti-war group.”

Returning to An Khe, Howard got caught up in the deactivation of the 4th Infantry. He recalled, “I was sent to the 101st Airborne at Phu Bai and put in charge of Army trucks used at a local rock quarry. At night we would man the bunkers. We’d sit on the bunkers to watch B-52 strikes, some over 10 miles away. We could feel the rumbles and saw the horizon turn a bluish color. Rockets and mortars paid us visits. If they landed on the other side of base I’d stay in bed, basically numb to the attacks, until the 1st Sergeant caught me. I’ll just say his perfectly chosen words from a colorful vocabulary kept me alive and awake for the rest of my tour.”

For Howard, Thanksgiving Day 1970 was indeed a special day to offer thanks: he was going home. The hell of Vietnam behind him; the hell of civilian life awaited his return. His final thoughts typify the stories of an entire generation that came home from an unpopular war.

“I went home to Tennessee with plans to attend college but I struggled with it. We’d been trained to kill but were offered no adjustment or down time….just go home, you’re on your own. When people that love and care for you say something is wrong then you should listen. Even dad suggested I see someone at the VA, well, I didn’t. I figured it was best to do it on my own. That was a mistake. I tried to join the VFW with other Vietnam vets but we were told our type was unwelcome and that we didn’t belong there. That still hurts.”

“It took me seven years to finish college and only received one offer of employment, Greyhound Bus. I came to Atlanta for the job in 1986 and have lived in Conyers ever since. I tried to interview for other jobs but the same five questions were always asked: Were you in Vietnam; what did you do; where did you serve; how long were you there, and did you ever kill anybody? You just got tired of it. That’s why a lot of Nam vets dug a hole for ourselves.”

“The government lied to us about Vietnam. The scars remain and some families are still dealing with M.I.A. issues. Politicians are always trying to govern but they really don’t, or won’t. Just take look at what’s going on today; the politicians are in Washington to help themselves, not us, and I don’t think they have our security as first priority. Veterans were offered a deal, but we got a raw deal. Career politicians have it made while our veterans continue to suffer.”

“We were told our fight was for freedom, but look how much freedom has been given away or taken away in the last few years. It’s troubling. I know for most veterans the worm turned and we are finally receiving the respect and honor that we earned, but I think about all our brothers that have passed away and didn’t live to feel or see all the respect and honor that they too earned. I especially mourn for 58,267 names on a long black wall in Washington, DC. Those are the heroes; we’re just the survivors.”

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran, columnist and freelance writer. You can reach him at aveteransstory@gmail.com or aveteransstory.us.