The Montford Point Marines were all black, separated from white Marines in basic training at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. These ‘men of color’ served their country in time of war yet most American businesses would not serve them. German POWs incarcerated on American soil during WWII were often shepherded to local towns for an American meal in an American restaurant. Any black soldiers on the guard detail would have to wait outside the American restaurant while the enemy POWs ate American food. The wacky parody of that American reality is too deep to fathom.

Virgil Weems’ funeral service was my first time to attend a black funeral in a black church, and attempts to pen a story on the experience eluded my talent. I struggled to find the right words to describe a black funeral at a black church because I’m white; simple and to the point. I deleted two rough drafts because the narrative was infiltrated with stereotype rubbish likened to a New York Times reporter tutoring Southerners on how to fry chicken or bake a pecan pie. Instead of gibberish, I decided to pen heartfelt honesty. So, here it is, and I pray my words show the proper respect to Virgil Weems, his family, and the church he loved so much.

I was born and raised a Lutheran, and will most likely push up grass as a Lutheran. Less formal than Catholic services, Lutheran liturgy is a mite too structured for most folks and a few of our hymns have often been labeled as non-narcotic sedatives. Religious formality is fine if devotion to your God requires conventionalism, but I know my dad had trouble staying awake during sermons. Then again, my dad could take a quick nap on a cactus plant during a dust storm. Nonetheless, before Pastor Armstrong-Reiner calls for my excommunication, please allow a brief defense of my faith. Lutheranism implanted the basic rules of life into my personality: right against wrong, good versus evil, obey the Ten Commandments, always respect the cloth, and memorize the Lord’s Prayer.

Lutherans do not ‘backslide’; we simply trip, fall down, and go ‘Boom’! Then we pick ourselves up, choose a better path, and with any luck use our God-given common sense not to flounder over the same obstacle least one be accused of stupidity. Tolerance based on moderation is a Lutheran attribute, but the scarcity of joie de vivre in song and sermon could use a good God-inspired shot in the arm. Not so at Shiloh Baptist Church.

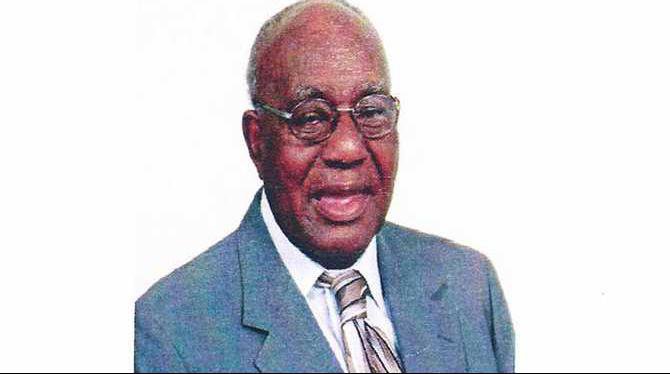

The spiritual message at Shiloh, in my unassuming opinion, is likened to a faith-inspired Physician of the Word checking a congregation for vital signs. In other words, if you are not tapping your feet or clapping your hands or cutting loose a random “Amen!’ then you may need to check your pulse because odds are you are no longer among the living. Virgil Weems’ service was precisely what the funeral program indicated: ‘A Goinghome Celebration.’ Now, a few words about a share cropper, a man of faith, an unyielding father figure, and a Montford Point Marine.

Let’s take a trip back in time, way back, to May 1, 1924. Virgil Weems is born in Locust Grove, the eleventh of 12 children. Like his dad, Virgil share-cropped until he received a letter of ‘greetings’ from Uncle Sam. Share-cropping was demanding work for little financial return yet a necessary way of life and survival for generations of poverty stricken Americans. Virgil’s daughter, Dr. Mamie Smith, recalled when she was a child, “As a little girl I followed my father in the fields while he plowed straight rows, one after the other. On occasion he would let me take a turn behind the plow but my rows zig-zagged all over the place. When I asked dad how he plowed so straight, he would always reply, ‘Pick out a spot in front of the mule and focus on that one speck. Don’t take your eyes off the goal. That will serve you well in life, too.’”

Drafted into the Army, Virgil was the only one in his recruitment group chosen for the Marine Corps. He confessed during our interview over a year ago, “I didn’t even know what a Marine was. When I asked them why I was chosen, they said I was too smart to be in the Army.” Trained by the selected few, Virgil was dispatched to the Pacific for the retaking of Guam, the bloodbath called Iwo Jima, and the brutal decisive battle for Okinawa. Reflecting on these islands of horror, Virgil softly said, “It was a dreadful thing. I lost a lot of friends on those islands, white and black. War is the equalizer, everybody bleeds the same color blood.” Honorably discharged in 1947, Virgil went home to raise a family and realize the American dream.

Imagine the journey from being born into a share-cropping household, being sent across the vast Pacific Ocean to fight against an enemy most likely from impoverished backgrounds much like himself, then returning home to see a transformation long overdue in Civil Rights, acceptance, respect, and a long membership and deaconship in a church filled with love and grace. Imagine. Just imagine. Experiencing 91 years of change — slow change in many cases, too fast of change in others — yet living to realize the dreams prophesied by the man from Selma come to fruition. Imagine, just imagine, the dreams of a share cropper, a father, a war veteran, a man of faith, a man most likely dreaming for his family and friends; not himself. Just imagine.

Imagine, too, the passing of the last WWII veteran, the last member of the Greatest Generation. That day is rapidly approaching. Every 90 seconds America loses one of its Greatest, and with their passing all of us lose a piece of history, a piece of America, a piece of the American dream. Virgil told me the story of his Montford Point Marine journey, but the narrative was only a small part of his 91-year journey. It’s true that young people possess the energy, but old people possess the experience, and the human experience, even in war, is the fabric that shapes mankind. Men like Virgil Weems have the experience to appreciate that the flipside of mankind is simply being a kind man.

Photos of Virgil faded in and out on three large video screens at Shiloh Baptist Church. Alongside one photo of a young man in uniform were the words: Another Soldier Comes Home. I respectfully disagree with the first two words. Virgil Weems was not just ‘another soldier’…….he was a Marine, a Montford Point Marine. And Virgil was so much more than a ground pounder, he was a ground breaker.

Can I get a witness?

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran, columnist and freelance writer. You can reach him at aveteransstory@gmail.com or aveteransstory.us.