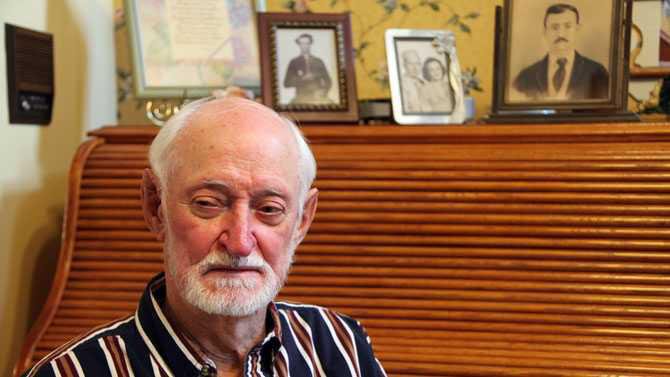

Grady Mullins was born the youngest of 12 children on June 28, 1926, in the rural farm community of Jasper. Back then large families ensured economic survival and the potential to go forth and multiply family genes. Political correctness meant you voted on Election Day; a cell phone was the one and only communication gadget at the state penitentiary, iPod was a slurred pronunciation for stuff in the cow pasture. Things were, well, different.

During our interview, Grady explained, "We were dirt poor farmers; and what we grew on the farm, by golly, we ate. All us youngins' had chores, and I sure wish I had a dollar for every cow I milked. You grew up fast, but in my mind I didn't become a real human being until June 28, 1942."

Erroneously believing I had a handle on his last comment, I asked Grady, "Is that when you joined the military?"

"Nope," Grady replied. "That's went I turned 16 and got my social security card and my driver's license." Some things, well, aren't different.

On December 7, 1941, the family radio informed Grady's people about the Pearl Harbor attack, and they realized their country was at war, even though most the good folks around Jasper didn't know where or what Pearl Harbor was. Of five brothers, four went to war. "People today don't realize what effect that had on families," Grady said. "Even the wives and mothers saved bacon grease to be used in explosives. We were all in this thing together."

Too young to enlist, Grady took a job in Atlanta at an iron works plant and built enormous steel double-doors for LSTs (landing ships) for two years. But the day Grady turned 18, he followed his brothers into war. At 6-foot 5-inches Grady was too tall for Army aviation, so in September of '44 he began a 17 week training course for combat infantry. The Battle of the Bulge in December of '44 cut short his training. Sent home for a five-day leave, on the fifth day his parents took their youngest son to the train station.

"I was the last son to go," Grady said. "I can still remember the grim look on my mother's face, and it was the first time I saw tears in my father's eyes."

Eventually assigned to the 66th Infantry "Black Panther" Division, Grady crossed the pond in style on the Ile De France, at that time the third largest luxury liner in the world, although, as Grady explained, "The Army took most of the "luxury" out of the liner." Another vessel, the converted Belgian passenger ship SS Leopoldville, transported another 2,500 men of the Black Panthers across the English Channel. Five miles short of its destination at Cherbourg, the SS Leopoldville was hit by a German torpedo. Fourteen officers and 748 enlisted men lost their lives.

Upon landing in France, Grady was sent with the 66th into a blocking position to suppress and/or eliminate 100,000 cornered but battle-hardened German soldiers in the Lorient and St. Nazaire pockets. The battle was a vicious but little-known melee far behind the Allied advance across the Rhine.

Grady explained, "The Germans had 88mm artillery mounted on trucks. They'd back up the trucks to the top of a hill and cut loose on us, then quickly retreat down the back side of the hill. In one fight a piece of shrapnel nicked my leg and embedded in a tree. I cut the piece of shrapnel out of the tree and put it in my pocket. I still have it to this day" There was no Purple Heart for Grady. "It was just a small cut," he stated. "A band-aid did the trick, and I was back in action."

In snow and frigid cold, the 66th pressed their aggressive tactics. Artillery duels were common, and deadly. In February, the 66th fired an average of 1,140 rounds per day. In March an average of 2,000 daily rounds fell on German positions. In April, the 66th lobbed 66,000 shells on the beleaguered enemy.

Grady asked me not to embellish his war experiences. "I fired my M-1 frequently but don't know if I ever hit anything," he said with a smile. "Things got a little nutty. We'd plant booby traps and mines then the Germans would dig them up at night and lay them out in a neat little line just to aggravate us the next morning. Grown men were dying out there, yet grown men still found time in war to play jokes on each other."

After the fall of Germany, the 66th traveled 700 miles to occupy 2,400 square miles of Reich territory, but the Black Panthers had hardly settled down when ordered back to southern France to help billet, feed, and process troops being redeployed to the Pacific through the port of Marseille.

"That was sorta of a lucky break," Grady said. "The Army had a point system and I had enough so-called ‘combat points' to keep me out of the Pacific. Plus, due to my experience in processsing troops the army offered me $350 to re-enlist for another year to help process out the soldiers coming home from the war. That was a lot of money back then."

Grady was sent to Camp Campbell, Ky. for his last year in the military to process out our returning veterans. A recipient of the Bronze Star and two campaign ribbons, he was discharged in December of 1946. Grady Mullins had made it home, as did all his brothers.

After the war he worked in his brother's road construction business. "Let me tell you about asphalt," he said. "It's hot and it's heavy. End of story." Striking out on his own in 1955, Grady went to work for a commercial airline that got its start crop-dusting in Louisiana. "People know it today as Delta Airlines."

Grady retired from Delta in 1989. He and his wife live within a rock-toss of the monastery on Highway 212 in Conyers. A farmer; an iron worker; a combat veteran; a construction man; a retiree from a great American corporation; another great example of the Greatest Generation.

Thank you for your service, Grady.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran and freelance writer. If you're on active duty, a veteran, or a member of the homefront and would like to be considered for a column, contact him at petemecca@gmail.com