Throughout the course of nearly 250 years of American Military History, only 3,468 service personnel have received the decoration, 621 of them posthumously. The award is called the Medal of Honor.

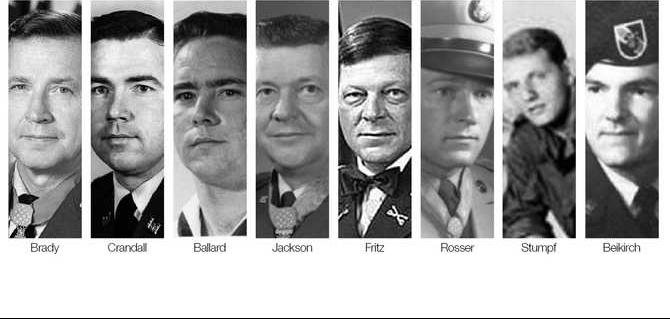

To meet and converse with just one of these rare individuals is indeed a privilege, but I had the honor of meeting and talking with 8 recipients of our nation’s highest award.

The occasion was sponsored by the Atlanta Vietnam Veterans Business Association. Approximately 250 veterans and friends packed the room. The iconic black Air Cavalry Stetson hat capped several craniums, some with outlandishly long feathers poking out of the hat band. The stories to follow are edited selections from the Congressional Medal of Honor Society, the recipients’ own websites, military publications, and in their own words. Our main speaker and master of ceremony and wittiness was Major General Pat Brady.

January 6, 1968: Thirty-two-year-old Major Patrick Henry Brady was on his second tour of Vietnam as a medevac pilot. When the call came, he volunteered to fly into dense fog to rescue injured soldiers in enemy held territory. Diving through thick fog and smoke, Brady maneuvered slowly along a valley trail and turned his Huey chopper sideward to use the backwash from his rotor blades to blow away the fog. Under heavy enemy fire, he landed in a riskily small LZ (landing zone) and evacuated 2 critically wounded soldiers. Dispatched to another ‘hot’ LZ covered in thick fog, Brady made 4 flights into the same embattled area and rescued all the wounded.

On his third mission, the audacious pilot landed at a site surrounded by the enemy. With his controls damaged and the Huey speckled in bullet holes, Brady flew into the area twice to rescue the wounded. He obtained a replacement chopper after being requested to rescue troops trapped in a mine field. One mine exploded and damaged the medevac Huey and injured 2 crewmembers. Undeterred, Brady managed to save 6 badly injured men. In a single day, Brady utilized 3 Hueys and rescued 51 seriously wounded soldiers.

Another chopper pilot, Major Bruce Crandall, flew into military history during the Battle of Ia Drang Valley in support of LZ X-Ray, Colonel Hal Moore’s renowned 1st Air Cavalry Division. After 4 flights by transport Hueys, the ground commander waved off further landings due to heavy enemy fire. Albeit, Crandall realized the situation was desperate. He returned to base, reloaded his Huey with ammunition and supplies, plucked a few volunteers to help evacuate wounded then flew the rest of the day and into the night, a total of 22 life-saving flights, mostly into intense enemy fire. His exploits are described in detail in Moore’s book, “We Were Soldiers Once….and Young.”

The U.S. Marines trust their lives in combat to Navy Corpsmen. Donald “Doc” Ballard was one of those angels of mercy. Serving with Marines in the Quang Tri Province area of Vietnam on May 16, 1968, Ballard had treated two Marines suffering from heat exhaustion and was returning to his unit from the medevac chopper when his company abruptly came under attack by the North Vietnamese Army. While directing aid to and treating wounded men, an enemy grenade landed in close proximity. Without hesitation, Ballard threw his body onto the grenade to protect his leathernecks.

The grenade failed to explode. Ballard casually got up then tossed the grenade away. It exploded harmlessly. Ballard received the Medal of Honor from then-President Richard Nixon and General Westmoreland in 1970.

On May 12, 1968, Lt. Col. Joe Jackson held his C-123 cargo aircraft in a holding pattern above the Special Forces camp at Kham Duc, near the Laotian border. The camp was fighting off a superior enemy force and would soon be overrun. A frantic evacuation was underway. Jackson listened to the radio chatter as an airborne command post controlled air traffic into the small air strip while forward air controllers called in air strikes against enemy targets. Smoke and flames and enemy tracers were clearly visible. When the last survivors were flown out, American fighter bombers were directed to obliterate the camp and any enemy occupants. Unfortunately, 3 U.S. airmen had been left behind.

One C-123 made an attempted landing/rescue but failed to spot the U.S. airmen and came under intense enemy fire. Throttling to full power for emergency takeoff, the crew saw the three Americans huddled in a ditch by the runway but it was too late to abort the takeoff. Jackson was asked if he would try a rescue. He didn’t hesitate. Jackson knew the enemy would expect the lumbering C-123 to follow the same flight path. So, why not fly it straight down in a nose dive from 9,000 feet?

Breaking his daredevil descent at tree top level, a stunned enemy finally opened up on the cargo plane. Dodging debris on the runway, Jackson applied the brakes and three very grateful airmen scrambled aboard. As they did, a 122mm rocket landed near the nose of the aircraft, certain death and destruction, yet the rocket failed to explode. Jackson taxied around the rocket and pushed to full throttle. Mortars rained down; a murderous crossfire of tracers lay ahead, enemy soldiers ran across the camp, but there was no turning back for Jackson. Finally airborne with his precious human cargo, one of the rescued U.S. airmen ventured into the cockpit and told Jackson that he undoubtedly had the biggest pair in the history of manhood.

Captain (then 1st Lt.) Hal Fritz was leading a seven vehicle armored column near Quan Loi, Vietnam when an enemy company caught their vehicles in a deadly crossfire. Fritz’s vehicle was hit and he was seriously injured. His platoon was surrounded and outnumbered. Without regard for his own life, Fritz jumped to the top of his burning vehicle to reposition his men and their vehicles. The enemy charged. Fritz manned a machine gun and raked the enemy ranks. Inspired, his men fought with tenacity to break up the attack. Within seconds, another enemy assault came within a few yards of the American position and threatened to overrun their defenses. Fritz, now armed with only a pistol and a bayonet, led a cluster of his men in a direct counter-assault that broke up the attack with heavy losses on the enemy. An American relief force arrived but positioned their forces incorrectly. Fritz, despite his own wounds, took charge and repositioned the relief force which effectively drove off the remaining enemy forces. He returned to his unit, assisted the injured yet refused medical attention until his wounded soldiers were safely evacuated.

Ronald E. Rosser was the second oldest of 17 children. One of Rosser’s brothers was killed early-on in the Korean War. Rosser sought revenge and joined the Army. On January 12, 1952, Rosser and his unit were assaulting a fortified hill near Ponggilli. Their unit was stopped by fierce small arms and automatic weapons fire, deadly accurate artillery and mortars, coming from two directions. Armed with a carbine and one grenade, Rosser charged an enemy bunker and wiped it out. Sprinting to the top of the hill, he killed two enemy soldiers, jumped into a trench and killed five more as he advanced. Rosser tossed his only grenade into another bunker and dispatched two other soldiers. Then he returned to his unit for more ammo and grenades.

He charged again, wiped out two more bunkers, then returned to his unit for a second time to replenish his supply of weapons. His third assault wiped out additional enemy strongpoints. As his unit withdrew, Rosser, although wounded, made several trips across exposed ground to help evacuate more seriously wounded Americans. Rosser single-handedly killed at least 13 enemy soldiers and saved many Americans.

Rosser remained in the Army. He obtained a rank of Master Sergeant, but retired after another brother was killed in Vietnam and the Army refused to grant him a combat assignment to Southeast Asia.

April 25, 1967: Squad leader Sergeant Ken Stumpf and his men were on a search and destroy mission near Duc Pho, Vietnam. Approaching a small village, they came under fire from North Vietnamese troops in a well-protected bunker complex. Three of Stumpf’s men fell. Without regard for his own safety, Stumpf ran through a hail of bullets to reach his wounded men. He rescued one then returned twice more to save the remaining soldiers.

Then Stumpf organized his soldiers and launched a determined assault against the enemy bunkers. Two bunkers were destroyed, but a third remained a serious threat. Stumpf grabbed extra hand grenades and dashed across open ground toward the machine gun nest. He reached the bunker, tossed a grenade into the aperture but the enemy grabbed the grenade and tossed it back. Stumpf took cover. After the grenade detonated, he pulled the pins on two more grenades, held them a few seconds then tossed the grenades through the aperture. The bunker was destroyed. Stumpf and the remainder of his unit then assaulted and overran the remaining enemy positions.

Green Beret combat medic Sgt. Gary Beikirch graduated from White Mount Seminary in 1975. He had planned to return to Vietnam and work in the missionary hospital in Kon Tum Province. South Vietnam fell before Beikirch could return to the people he loved: The Mountain People, the Montagnards.

April 1, 1970: the peaceful Montagnard camp of Dak Seang came under attack by three regiments of NVA soldiers. Inside Dak Seang, Montagnard villagers, mostly women and children, and 12 Americans absorbed the onslaught. Artillery and rockets exploded inside the camp before the enemy ‘human wave’ attack hit the camp. As his Montagnard assistants treated the injured, Beikirch manned a mortar until it was knocked out of action. He then manned a machine gun, but Montagnard casualties and American wounded had overwhelmed his assistants.

Running through heavy enemy fire, Beikirch treated many injured and was wounded several times. Hit by shrapnel, including a fragment near his spine that partially paralyzed him; his Montagnard assistants carried Beikirch from one position to another, giving aid to the wounded and dying. He was hit in the side giving mouth-to-mouth resuscitation to a native fighter; then took a round to the stomach. Beikirch finally lost consciousness.

His thoughts after passing out: “….my personal memories are a swirling stream of sporadic events, seeing medevac choppers being shot down as they tried to get me out…strong arms reaching down and pulling me safely inside a chopper, the face of a young medic shocked to see that I was still alive, but telling me I was going to be OK, being thrown onto a litter and rushed into an operating room, the IVs in my arms and neck, catheters in every opening of my body, the lights, shouting….and then, darkness.”

American veterans. If you see one, if you know of one, walk up and just say ‘thank you’….they have at least earned that.

Pete Mecca is a Vietnam veteran, columnist and freelance writer. You can reach him at aveteransstory@gmail.com or aveteransstory.us.